- Scala is an acronym for “Scalable Language”

object Hello extends App {

println("Hello, World!")

}

object Hello {

def main(args: Array[String]): Unit = {

println("Hello World")

}

}

- In Scala, variables can either be mutable or immutable. An immutable variable is a variable that cannot be modified after it has been created.

- To create an immutable variable, you preface it with the val keyword and mutable variables are created with the var keyword.

val first: String = "Hello"

println(first)

first = "Something Else" // Error -> reassignment to val

- Scala supports Type Inference, which means the Scala compiler infers the type of a variable.

- To see this in action change the declaration of the first variable by removing the type:

var first = "Hello"

- What you will notice is that the program still compiles. The Scala compiler has inferred first as a String because it was assigned a String value.

- This is different than a dynamic language like JavaScript, which allows any variable to contain any value, e.g. first set a variable to an integer value then change it to a string.

- In Scala you cannot change the type of the variable after it has been declared. For example, try assigning first to a number:

first = 2 // Error -> type mismatch; [error] found : Int(2); [error] required: String

- Another feature that makes Scala unique is that it is fully expression-oriented.

val second = {

val tmp = 2 * 5

tmp + 88

}

- This assigns a value of 98 to second. Notice that it does not require an explicit return statement and instead takes the last line to be the value returned.

- In the same way, an if-else is an expression in Scala and yields a result.

val second = 43

val displayFlag = if (second % 2 == 0)

"Second is Even"

else

"Second is Odd"

CLASSES AND OBJECTS

- Scala is a pure object-oriented language. Conceptually, every value is an object and every operation is a method call.

class Recipe(calories: Int) {

println(s"Created recipe with ${calories} calories")

var cookTime: Int = 0

}

- This creates a Scala class called Recipe with a constructor that takes calories as a parameter.

- Unlike Java, the constructor arguments are included in the class definition. Then any expressions in the body of the class are considered part of the “primary constructor”, such as the println.

- In addition to constructor parameters, a class has values and variables, such as the variable cookTime in the previous example.

- Values are declared using the val keyword and variables are declared using the var keyword.

- By default the constructor parameters for a class are only visible inside the class itself and only values and variables are visible outside of the class.

object Hello {

def main(args: Array[String]): Unit = {

val r = new Recipe(100) // outputs Created recipe with 100 calories

println(r.cookTime) // outputs 0

r.cookTime = 2

println(r.cookTime) // outputs 2

println(r.calories) // // This will produce an error - value calories is not a member of recipe

}

}

- To promote the constructor parameters use the prefix val or var depending on whether they are supposed to be immutable or mutable. For example, change the Recipe class definition to:

class Recipe(val calories: Int) {

- Then try printing out the calories again in the Hello object. Now the compiler should be happy.

- Method definitions in Scala start with the keyword def followed by the name of the method and its parameters.

- The return type of the method can be inferred, just like with variables, when not explicitly declared.

- The return value is the last line of the method.

// Declares method that returns an Int - Int return is optional.

def estimatedEffort(servings:Int): Int = {

println("estimating the effort...")

servings * cookTime * calories

}

- We can also create subclasses by extending abstract or non-final classes just like any object-oriented language.

- The one difference is the constructor parameters of the class being extended need to be passed in as well.

class Food(calories: Int)

class Salad(val lettuceCalories: Int, val dressingCalories: Int)extends Food(lettuceCalories + dressingCalories)

- When extending a class we can also override members of parent classes.

class Food(calories : Int)

class Salad(val lettuceCalories : Int, val dressingCalories : Int) extends Food(lettuceCalories + dressingCalories)

// Example of Overriding Methods

class Menu(items : List[ Food ]) {

def numberOfMenuItems() = items.size

}

// Dinners only consists of Salads

class Dinner(items : List[ Salad ]) extends Menu(items) {

// Overriding def as val

override def numberOfMenuItems = 2 * items.size

}

- Scala does not have a static keyword like Java to mark a definition as a static (singleton) instance.

- Instead it uses the object keyword to declare a singleton object.

- All the members defined inside the object are treated as singleton members and can be accessed without creating an explicit instance.

- A common use of the singleton object is for declaring constants.

- Objects are commonly used to hold factory methods for creating classes.

- This pattern is so common that Scala declares a special method definition for this called apply.

- The apply method can be thought of like a default factory method that allows the object to be called like a method.

- For example, inside the Recipe.scala file, add an object above the class definition:

object Recipe {

def apply(calories: Int) = new Recipe(calories)

}

class Recipe(calories: Int) {

println(s"Created recipe with ${calories} calories")

var cookTime: Int = 0

}

object Hello {

def main(args: Array[String]): Unit = {

// This call refers to the Recipe object and is the same as calling Recipe.apply(100)

val r = Recipe(100) // apply method is called by default

println(r.calories) // outputs 100

}

}

- What is interesting about the use of the Recipe object here is that no method had to be specified—apply was called by default.

- An object is considered a companion object when it is declared in the same file as the class and shares the name and the package.

- Companion objects are used to hold the static definitions related to class but do not have any special relationship to a class.

- What is interesting about the use of the Recipe object here is that no method had to be specified—apply was called by default.

Case Classes

- Case classes in Scala are classes on steroids.

- When the Scala compiler sees a case class, it automatically generates helpful boilerplate code to reduce the amount of code for common tasks.

- The only difference is the class definition has the keyword case before it:

case class Person(name: String, age: Int)

When we prefix a class with case, the following things happen:

- Constructor parameters (such as name and age) are made immutable values by default. Scala does this by prefixing all parameters with val automatically.

- Equals, hashCode, and toString are generated based on the constructor parameters.

- A copy method is generated so we can easily create a modified copy of a class instance.

- A default implementation is provided for serialization.

- A companion object and the default apply factory method is created.

- Pattern matching on the class is made possible.

- Because Person is defined as a case class it will be compiled into something like the following:

class Person(val name: String, val age: Int) { ... }

object Person {

def apply(name: String, age: Int) = new Person(name, age)

...

}

- Here object Person is the companion object for class Person.

- The Person class can then be created without using the new keyword.

val p = Person("John", 26) // same as Person.apply("John", 26)

- We can also define additional apply methods inside classes and objects.

TRAITS

- Traits can be viewed as an interface that provides a default implementation of some of the methods (Java 8 added something similar with default methods on interfaces).

- In contrast to classes, traits may not have constructor parameters and are not instantiated directly like a class. They can be used similarly to an abstract class:

// Declaring a trait with an abstract method

trait Greetings {

def sayHello : String

}

class IndianGreetings extends Greetings {

override def sayHello : String = "Indian"

}

- The HelloGreetings class extends the Greetings trait and implements the sayHello method.

- Traits can also be used to provide methods and variables that are mixed into a class instead of being extended. Let’s make this example more interesting by adding one more trait.

// Declaring a trait with an abstract method

trait Greetings {

def sayHello : String

}

class IndianGreetings extends Greetings {

override def sayHello : String = "Indian"

}

trait DefaultGreetings {

def defaultHello = "Hello"

}

class GermanGreetings extends Greetings with DefaultGreetings {

override def sayHello : String = "German"

}

object Hello {

def main(args : Array[ String ]) : Unit = {

val g = new GermanGreetings

g.sayHello // output : German

g.defaultHello // output : Hello

}

}

- The GermanGreetings extends both Greetings and DefaultGreetings.

- The later is mixed-in to provide the default greetings behavior.

- Traits can also be mixed-in at the instance level:

val j = new IndianGreetings with DefaultGreetings

j.sayHello // output : Indian

j.defaultHello // output : Hello

- This particular instance of IndianGreetings will have both sayHello and defaultHello methods.

FUNCTIONS

- Functions are similar to a method in Scala except that a function is attached to a class. Instead, functions are usually declared as an argument to another method.

- Functions are also values that are assigned to variables, and functions also have types.

- Methods are not values. These function values can then be passed around like other variables.

- The following creates a function that finds the successor of any given parameter and assigns that function to the succ variable.

// Creates a function that takes an Int as a parameter and returns Int.

// The variable type in Scala is formally declared as Int => Int

val succ = (foo: Int) => { foo + 1 }

println(succ(100)) // 101

- Here, foo is the name of the parameter and what comes after => is the body of the function.

- We can also pass functions as a parameter to other functions and methods.

- In the following example, the adjustAndLog method takes two parameters, an integer value, and a function that takes a single Int, and returns an Int.

object Hello {

def adjustAndLog(someInt : Int, adjust : Int => Int) = {

println(s"Adjusting $someInt")

adjust(someInt)

}

def adjustAndLog2(someInt : Int, adjust : Int => Int) = {

println(s"Adjusting $someInt")

adjust(someInt*2)

}

def main(args : Array[ String ]) : Unit = {

val sum = adjustAndLog(100, (i : Int) => i + 10)

println(sum) // 110

val sum2 = adjustAndLog2(100, (i : Int) => i + 10)

println(sum2) // 210

}

}

COLLECTIONS

- Scala collections come in many forms— they can be immutable, mutable, and parallel.

- The language encourages you to use immutable collection APIs and imports them by default.

- Here are a few examples of how collection classes can be instantiated:

def main(args : Array[ String ]) : Unit = {

val indexedSeq = IndexedSeq(10,20,30, 30, 20, 10)

println("indexedSeq :: " + indexedSeq) // indexedSeq :: Vector(10, 20, 30, 30, 20, 10)

val vectors = Vector(10,20,30, 30, 20, 10)

println("vectors :: " + vectors) // vectors :: Vector(10, 20, 30, 30, 20, 10)

val sets = Set(10,20,30, 30, 20, 10)

println("sets :: " + sets) // sets :: Set(10, 20, 30)

val maps = Map("Java" -> 1, "Scala" -> 2, "Java" -> 3, 4 -> "Kotlin")

println("maps :: " + maps) // maps :: Map(Java -> 3, Scala -> 2, 4 -> Kotlin)

val range = 1 to 10

println(range) // Range(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

}

- Now let’s see how we can perform some common tasks using Scala collections.

TRANSFORM ALL THE ELEMENTS OF THE COLLECTION:

val xs = Vector(10, 20, 30, 40)

// Map executes the given anonymous function for each element in the //collection

val newList = xs.map(x => x / 2)

println(newList) // outputs new sequence Vector(5, 10, 15, 20)

println(xs) // outputs the original collection because it is immutable // Vector(10, 20, 30, 40)

Filtering:

val xs = Vector(1, 2, 3, 4, 5).filter(x => x % 2 != 0) //odd numbers

println(xs) // outputs new collection Vector(1, 3, 5)

GROUPING ELEMENTS OF COLLECTIONS BASED ON THE RETURN VALUE:

val groupByOddEven = Vector(1, 2, 3, 4, 5).groupBy { x => if (x % 2 == 0) "even" else "odd" }

println(groupByOddEven) // Map(odd -> Vector(1, 3, 5), even -> Vector(2, 4))-

SORTING:

val lowestToHighest = Vector(3, 1, 2).sorted

println(lowestToHighest) // outputs Vector(1, 2, 3)

- Scala provides mutable counterparts of all the immutable collections.

- For example, the following creates a mutable sequence of numbers:

val numbers = scala.collection.mutable.ListBuffer(10,20,30)

println(numbers) // ListBuffer(10, 20, 30)

numbers(0) = 40

println(numbers) // ListBuffer(40, 20, 30)

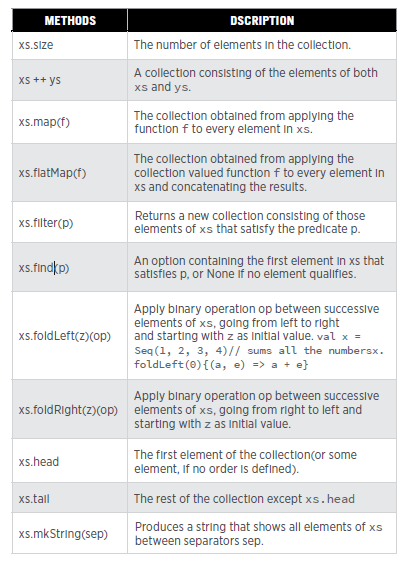

- Here are some of the useful methods defined in the Traversable trait that are available to all collection types:

CONCURRENCY:

- Scala provides developers with a higher level of abstraction with Futures and Promises.

- Future is an object holding a value that may become available at some point.

- This value is usually the result of some other computation.

- A Future object is completed with either a value or an exception.

- Once it is completed it becomes in effect immutable—it can never be overwritten.

- The simplest way to create a Future object is to invoke the Future method, which starts an asynchronous computation and returns a Future holding the result of that computation.

- The result becomes available once the Future completes.

import scala.concurrent.ExecutionContext.Implicits.global

import scala.concurrent.Future

def someTimeConsumingComputation(): Int = { 25 + 50 }

val theFuture = Future { someTimeConsumingComputation() }

// OR

val someTimeConsumingComputation1 : Int = { 25 + 50 }

val theFuture1 = Future { someTimeConsumingComputation1 }

- The line import ExecutionContext.Implicits.global above makes the default global execution context available. Need to be imported manually.

- An execution context is a thread pool that executes the tasks submitted to it.

- The Future object uses this execution context to asynchronously execute the given task.

- In this case the task is someTimeConsumingComputation.

- The statement Future { … } is what actually starts Future running in the given execution context.

- Once a Future is completed, registering a callback can retrieve the value.

- A separate callback is registered for both the expected value and an exception to handle both possible outcome scenarios:

theFuture.onComplete {

case Success(x) => println(x)

case Failure(t) => println(s"Error: ${t.getMessage}")

}

Example of Future:

import scala.concurrent.ExecutionContext.Implicits.global

import scala.concurrent.Future

object Hello {

def main(args : Array[ String ]) : Unit = {

val someTimeConsumingComputation : Int = { 25 + 50 }

val theFuture = Future { someTimeConsumingComputation }

theFuture.onComplete {

case Success(x) => println(x) // 75

case Failure(t) => println(s"Error: ${t.getMessage}")

}

val anotherFuture = Future { 25 + 50 }

anotherFuture.onComplete {

case Success(x) => println(x) // 75

case Failure(t) => println(s"Error: ${t.getMessage}")

}

val anotherFuture2 = Future { 2 / 0 }

anotherFuture2.onComplete {

case Success(x) => println(x)

case Failure(t) => println(s"Error: ${t.getMessage}") // Error: / by zero

}

}

}

- The following line will complete the Future with exception:

val anotherFuture = Future { 2 / 0 }

- Futures are very handy tool to run multiple parallel computations and then compose them together to come up with a final result.

FOR-COMPREHENSIONS:

- The for expression in Scala consists of a for keyword followed by one or more enumerators surrounded by parentheses and an expression block or yield expression.

- The following example adds all the elements of the first list with all the elements of the second list and creates a new list:

val ab = for {

a <- aList if (a % 2) == 0

b <- bList

} yield a + b

println(ab) // Output : List(11, 10, 9, 8, 13, 12, 11, 10) => 2+9, 2+8, 2+7, 2+6, 4+9, 4+8, 4+7, 4+6

- The if condition after a <- aList is called a guard clause and it will filter out all the odd numbers and only invoke aList for even numbers.